Review of 2009/10 Auerbach and Bacon exhibitions/books

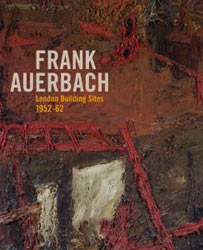

‘Frank Auerbach. London Building Sites 1952-1962’

Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, 16 October 2009-17 January 2010. Accompanying catalogue with essays by Barnaby Wright, Margaret Garlake and Paul Moorhouse, London 2009 ISBN 978-1-90347-094-7

Frank Auerbach

William Feaver, New York 2009 ISBN 978-0-8478-3058-9

‘Francis Bacon. A terrible beauty’

The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, 28 October 2009-7 March 2010; Compton Verney, Warwickshire, 27 March-20 JulyAccompanying book Göttingen 2009 ISBN 978-3-86930-027-6

‘Francis Bacon: Early works’

Room 8, Tate Britain, London

Purely abstract art produced by British artists has not troubled the scorers in the 20th-century art world. All the great art produced in the British Isles during the 20th century was, to a greater or lesser extent, figurative. Recently it has been possible to see examples of some of the best work produced during the century in important exhibitions and books.

Frank Auerbach began his life in 1931 as a German. He came to England in 1939, but did not see much of the bombing which his countrymen were busy inflicting on the cities of England. By 1952 he was ready, after a long artistic training, to paint, among other things, the redevelopment of various London bomb sites. Some commentators have remarked upon the difference between Auerbach’s approach to the destruction of London and that of someone like John Piper, steeped in nostalgia and grief for the maimed buildings. But it is surely obvious that Auerbach had no such nostalgia or grief. He had no interest in or empathy for the symbols of England’s past because he wasn’t English and was too young to have experienced at first hand the process of their destruction.

Indeed, apart from the event that caused these sites in the first place – their bombing – I do not get any impression that the War had anything to do with Auerbach’s vision of what he was trying to achieve with these pictures. What interested him was the artificial disturbance of the earth and the creation by man of a structure out of that disturbed earth. Commentators may choose to load the pictures with their own interpretations of the pictures based on War damage and the shocking effect on a cityscape of bombing, but it may be better just to treat them as pictures of building sites, formally exploring what oil paint can be made to do in such circumstances, especially paint being applied against the particular intellectual backdrop of Existentialism that affected England in the 1950s. As Paul Moorhouse explains in his catalogue essay, writers and artists in the ’50s were, in many cases, influenced in the way they went about their artistic discoveries by reading works by Sartre, Camus and de Beauvoir; and it is likely that Auerbach took some influence from these sources as well as from the painting style of Bomberg.

The pictures range over a period 1952-62. With the help of contemporary photographs and the artist’s own drawings where available, and after some intense scrutiny, it is possible to work out the image which lies beneath or in the paint. In some cases the famous Auerbach paint-thickness is notable and not ineffective in the context of these particular paintings. Mounds of disturbed earth painted in mounds of earth-coloured paint are, it has to be said, somehow helped as images by being thickly painted. The more successful pictures, to my mind, are the later ones. In the Shell Building Site: from the Thames (of 1959) and in the Oxford Street Building Sites (of 1960) the artist seems to me to have reached nearer to achieving an image of struggle and rebirth, if that is indeed what he was aiming for. The tensions involved on a building site in men wrestling with the ruptured earth so as to produce order – grids of steel girders perhaps – out of chaos is what Auerbach has communicated to this viewer. Painting tension and the controlling of chaos may be thought not to be easy subjects for an artist and it would be fair to say about Auerbach generally that he has never been an easy artist to engage with and he has certainly given the impression of never finding it easy to produce his work in the first place.

The catalogue is attractively produced, with an excellent essay by Barnaby Wright, a strangely architectural essay by Margaret Garlake and the essay mentioned above by Paul Moorhouse, who also helpfully integrates an account of Kossoff ’s early development alongside that of Auerbach. Lots of helpful reproductions of drawings, preparatory works and photographs support the main catalogue of the building site pictures themselves. The book is a useful addition to the growing field of Auerbach studies.

William Feaver’s book is a gorgeous, important production. Auerbach has already received some high-quality attention from one great art critic, Robert Hughes, and now he is blessed by serious attention from another. He surely deserves such attention. While he was not 20th-century Britain’s most important artist – Bacon ended the century with that prize firmly in his pocket – one has to acknowledge the seriousness of the way in which Auerbach approaches the challenges which he sets himself. He is a professional artist. He works hard, all the time, and always has done. He worries away at subjects and effects until he feels comfortable with them. He no doubt engages with the commercial world in the sense that he sells his pictures through a gallery, but he does not allow his private life to become a distracting construct in its own right, as Bacon did. His work is apparently what concerns him above all and it is that level of dedication which merits at least serious attention.

Feaver’s book contains a catalogue of the large quantity of work which Auerbach has produced over many years. Although he works slowly, he must surely work on a number of canvases at the same time, because he has produced a lot of pictures. A benefit of seeing the pictures set out complete and in chronological order is that one sees the trajectory of the work over a long period. Without such a compilation in the case of a living artist it can be very difficult to get the life’s work in perspective. Clearly Auerbach has been obsessive about a comparatively restricted number of subjects: the portrait heads, the model studies, the townscapes around Camden, the char-coal sketches and so on.

While many are in oil, there are many powerful portraits done, particularly early in his career, in charcoal and chalk on paper. These to me indicate what Auerbach must at least partly have been trying to achieve with his portraits. Stripped of the clotting which inevitably accompanies his method of working in oil, they show his ability to explore, and indeed to achieve, an image of a human face which delivers a passionately captured intensity. In oil this is harder to achieve and the danger, as with so many artists working over a long period, in a style which has been recognised as theirs and which has been critically received and accepted, is that the style becomes a caricature. It grieves one to say it about such an important artist, but is there anything more to say now when he paints a head? Hadn’t he said what he was going to be able to say by some time in the 1970s? On the other hand, I think he has continued to expand his impact in the townscapes, particularly in his apparently increasing exploration of colour. Some of the pictures of Park Village and Mornington Crescent painted in the 2000s do seem to be developments on the Mornington Crescents of 1966, for example: not better, but differently expressed, both in colour and in fluidity of technique. The later works are those of an old and experienced artist at the top of his game.

The book itself is a joy to handle. All credit to Rizzoli for this. One never knows which reproductions in any book most closely resem-ble the works themselves. In Auerbach’s case one can get a different impression from Feaver, the ‘Building Sites’ catalogue and the older Hughes monograph, but there we are.

The exhibition and books leave one asking various questions which do not seem to have been answered so far, and which could perhaps form the basis of future exhibitions or explorations. It would be instructive to see an exhibition giving full and equal weight to Bomberg, Auerbach and Kossoff. I feel instinctively that poor, so often neglected, Bomberg would be the ‘winner’ of that event, with his huge range of subjects and accomplishments. Also, what is to be made of the relationship between the work of Auerbach and Bacon? The heads, the naked bodies, even occasionally the landscapes produce some sparks of friction between the two careers; the multiple pictures, apparently in series, of the same subjects; even it seems the concept of ‘cages’. Here is Helen Lessore, Auerbach’s first dealer, quoted on page 31 of the exhibition catalogue: ‘Part of his procedure (making the cage) involves an arbitrary limitation of means.’ Something like that could be written about Bacon’s cages. How much did they look at each other’s work during the period when they were friendly, or how much were they both drawing upon shared sources, especially perhaps Rembrandt, Sickert and Soutine?

Finally, as a thought prompted by Auerbach and Bacon, when is something important going to be said or done about the curious relationship between certain key 20th-century British artists and their actual places of birth? Bacon’s ‘Irishness’ is currently being explored in Dublin, no doubt keen to claim him after the capture of his studio, and it seems to me that Auerbach’s Germanness has to be acknowledged, but not perhaps as much as Freud’s. Even now, listening to interviews with Freud, he still, after leaving Germany over 60 years ago, has a distinct German note to his accent; to what extent, if any, is he a British artist? Or is nationality irrelevant? The point gets harder to dismiss to the extent that the artist in question spent longer in the other country – German examples would be Bloch or Uhlman, both of whom left Germany as adults. Polish examples would be Adler or Herman. The other way round, it no doubt pains Irish art historians to admit that the great figure of Irish 20th-century art, Jack Yeats, was born in London.

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin in 1909 (the same year that Sir Hugh Lane was knighted) at 63 Lower Baggot Street. He was the child of middle- or even upper-middle-class Protestant English parents and there was nothing Irish or even Anglo-Irish about him. After he left Ireland at the age of about 16, he hardly returned, almost certainly never after 1939. Many British artists (a number of them friends or acquaintances of Bacon) visited Ireland to paint after the War, including Freud, Vaughan, Burra, Agar, Hillier, Colquhoun and Macbryde, Weight, Bawden, Uhlman, Piper, Ayrton, Lewis and Craxton; but not Bacon. He certainly does not seem to have expressed any interest in or affection for Ireland and it is a nice quirk of fate that now yokes him to Dublin through the arrival of his studio at the Hugh Lane Gallery. (I note that a photograph of the few books on Bacon’s bookshelf showed that he had a biography of Oscar Wilde.)

Just as with the long-running saga over the Hugh Lane pictures and the competing claim on them between Dublin and London, there now, since the arrival of his studio, seems to be some sort of cultural imperial battle opening up between Dublin and London over who can claim Bacon the most – before that Dublin did not concern itself with him too much, apart from a show in 1965. Now we have seen the Tate’s third great retrospective for him, in 2009, following those in 1985 and 1962, closely followed by the Hugh Lane’s second big exhibition about him in recent years – the previous one being called ‘Francis Bacon in Dublin’ in 2000. No sooner has the latest show opened in Dublin than the Tate responds with a very unusual little show in its Room 8, showing very rarely seen early works from the 1920s and 1930s.

The battle also seems to extend to the written word, in the analysis of the contents of the studio. Our own Martin Harrison has developed his platform with ‘In Camera: Francis Bacon, Photography, Film and the Practice of Painting’ in 2005 and ‘Incunabula’ in 2008; whilst Barbara Dawson (director of the Hugh Lane) and Margarita Cappock (Head of Collections at the Hugh Lane) have published ‘Francis Bacon’s Studio at the Hugh Lane’ in 2001 and Margarita Cappock has published ‘Francis Bacon’s Studio’ in 2005. In any event, Barbara Dawson and Martin Harrison have come together on this occasion by co-curating the exhibition and both featuring in the accompanying book. Delving into the archaeology of the studio, whether by Irish or English writers, is simply never going to end and books trickle out based upon an increasingly detailed analysis of the detritus of that studio. Whilst this has produced many interesting insights into Bacon’s sources and methods, one sometimes steps back to wonder which other 20th century artist gets analysed like this? Does anyone care which magazines Freud has read, if any, over the years, or whether he wrote lists on the endpapers of his books? If these sorts of analytical techniques are so relevant to a study of Bacon, why are they not employed by students of other artists to the same extent? It would surely be possible to pursue the working conditions of some other 20th century British artists in this way, where studio conditions or archive material have survived, but I am not aware that it is being done.

Still, historiographers of the Bacon industry are going to thrive for many years, as one can begin to look forward to writing about those who write about Bacon almost as much as writing about the man himself. It would, for example, be possible to torture David Sylvester’s writings on Bacon, and his fixation with him, to make them reveal something about their relationship and the extent of the rôle played by Sylvester in inventing the Bacon myth. There has not been too much seen in that direction yet, but it is fruitful ground. Will all the footling things which Bacon said about art and about his work – all of them – turn out to be thoughts of Sylvester, shaping up his man to be the thinking artist of 20th century Britain? I fear so. I also suspect that Sylvester put the virtually uneducated Bacon into contact with the sort of middlebrow classics he liked to quote for ever afterwards, such as little bits of Aeschylus in translation and so on. Bacon the profound thinker is really a hard Bacon to swallow.

Anyway, as I have said before when reviewing things about Bacon, some of those working on him are astute and careful critics and they produce work worthy of respect and attention. Martin Harrison is co-curator of the Dublin exhibition and has developed a large and well-deserved reputation as a man of ruthless factual accuracy and carefulness. (He is also an extremely generous man when asked for help, as this writer can vouch.) I long for the day when he allows him-self to go into print with comments on the aspects of Bacon’s past which do not stand up to too much scrutiny. It can be done without impugning the work. It has to be done sometime by somebody.

For all the frustrations generated by the industry growing up around Bacon, the work is always fascinating. The Hugh Lane show is a great treat in this respect. There are works with which I was not familiar (and which were certainly not at the Tate last year) and the room with the damaged pictures is extremely novel – interesting, as are the paint samples used to explore his technique. Bacon destroyed lots of pictures, but the archaeologists found in the studio that he sometimes left the cut-out bits lying about. And so in some cases they have the cut-up pictures and some of the missing bits. It can never be possible to be sure in each case why he defaced a picture, but studying the damage inflicted in particular cases is surely a legitimate way of trying to engage with his creative thinking: to glimpse the creative process through the artist’s own eyes.

There can be little doubt that Bacon was a passionately engaged creative thinker working deceptively hard at his pictures to produce effects which he planned and developed and which, in the end, left little to chance, despite what he nonsensically claimed.

Room 8 is interesting in a different way, with early works and some rugs and a screen painted by him. In the 1920s and ’30s he was signing his work. It would, of course, be fascinating to get more material about his painting activities in the years leading up to the first great triptych exhibited in 1945. Where did it spring from? What kind of work led up to it? For the things in Room 8 predate but do not presage what might be called the mature Bacon style that burst into the Lefevre Gallery in April 1945. The possibly influential role layed by the Australian artist, Roy de Maistre, has not been fully explored. There are tantalising glimpses of early works by Bacon in the background of some of de Maistre’s own pictures from the pre-War period. Unfortunately, until Sylvester came along at the end of the 1940s, and especially the 1950s, and gave Bacon something to say about his thoughts on art, we have nothing substantial from the artist himself to say what he was about, although there are glimpses in the Bacon letters which survive from the 1940’s.

In 1953 Bacon was made to pretend that he was impressed by Matthew Smith’s work, in the infamous ‘Painter’s Tribute’ at the front of the catalogue to a big Smith retrospective at the Tate. It was almost certainly written by Sylvester and basically amounted to a sort of manifesto of what Sylvester would make Bacon say about his own work over and over again ad infinitum (at the Hugh Lane Gallery there plays on an endless loop the Bacon/Bragg interview of 1985 in which Bacon is still mouthing the same old stuff over 30 years later).

The book which accompanies the Hugh Lane show has essays by a variety of people, as well as a thorough catalogue of the pictures on display. It is striking how a number of those writing comment on how inconsistent and unreliable were many of the things Bacon said about his own work. How his attitude towards apparently key aspects of his work did not so much consciously change, but more slid about, depending upon the impression he wanted to give. Examples are his varied responses to questions as to whether his work contained elements of ‘violence’: sometimes he said it did, sometimes he said it did not. He liked to say the elements of his paintings came by chance, but the technical analysis of his painting style, which is extremely revealing, shows that, while this may have been an important element to his work in the early days, it quickly became irrelevant. Bacon became a master of technique and clearly understood and controlled the outcome of his efforts on the canvas very carefully and effectively, but one would never know this if one relied upon the nonsense which he uttered to interviewers. He was also a master of obfuscation.

There are various reasons why Bacon the talker was so unreliable. It may have been a deliberate game intended to confuse analysis. He probably thought that art criticism could come to its own conclusions without his telling it what to think. He may also have believed that obscurity did no harm to reputation and, therefore, sales. There is also the rather sad thought that – barely educated and totally without artistic-training as he was – he wanted (and was encouraged by Sylvester to want) to be regarded as an intellectual artist, fizzing with creative and necessarily obscure thoughts about the indefinable nature of the creative process. Well, maybe he succeeded in whatever he wanted to achieve. Certainly during his life he seemed to keep a tight grip on the way in which he wanted his work to be received, but the critic who ignores much of what he said may produce a more balanced view of his work, approaching more closely an objective assessment of Bacon’s achievements.

This is a good book to accompany the exhibition. All the different contributions are crisp and to the point and all have interesting things to say about the different aspects of Bacon’s art that they are writing about. The area of Bacon commentary has become extremely crowded, with one’s bookshelf already groaning from the weight of Bacon studies, and so contributing anything original is in itself a fine achievement.

The older artist always mentioned as being someone whose work Bacon admired was Matthew Smith. The Guildhall Art Gallery in the City is not normally associated with 20th-century British art, but, by a quirk of fate, it holds an enormous collection of Smith’s work. In total it has over 1,000 paintings, drawings and watercolours by him, comprising the work left in the artist’s studio on his death in 1959 and presented to the City of London Corporation by his heir, Mary Keene, in 1973.

The exhibition was certainly extensive, and quite fascinating. The fact that it consisted of work from his studio probably skewed it a little towards his later work, rather than being a genuine attempt to cover his long painting career, but the overall effect was impressive.