There is a new exhibition opened at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge of Craxton’s work. I am not sure what has particularly led to the show being put on there, although it may have something to do with the enthusiastic new young Director, Tim Knox.

In any event, it is a welcome airing for Craxton’s work, which has not been widely seen in a public gallery since his 1967 Retrospective at the Whitechapel at the behest of Bryan Robertson. There was a small show at Tate Britain a few years ago, but that was not attempting to be comprehensive.

A problem in surveying the artist’s career is that it was a very long painting career indeed, encompassing various different styles. In his early days, during the War and with the huge power of Peter Watson’s wealth and encouragement behind him, he was instantly recognised as a purveyor of whatever was meant by Neo Romanticism. But he was always more than that, with a brilliant drafting skill and an interest which rapidly developed in all sorts of different directions.

Once he started to visit Greece, and particularly Crete, where he later bought a house, his colours and subject matter developed yet further. At the same time he glided out of the public view. Watson, who paid for a little book on the artist in 1948, written by Geoffrey Grigson, died in 1956 and Craxton spent increasingly long periods out of the English public’s eye. This inevitably meant that his work was treated as something of a curiosity in English art reviewing circles. It also meant that when the artist started to show in England in later years, his reputation had a bit of catching up to do. Moreover, his style had changed. One easily detects the influence of the Greek artist Ghika on certain periods of the work, but there were no doubt multiple influences going on in a way which made Craxton’s work very different from that of his English contemporaries.

Now the art market is increasingly marking his prices ever higher and it may be that this trend will continue and take him way up the English 20th C painters’ league tables.

It is impossible to mention Craxton’s development without emphasising the influence of Watson. Craxton dedicated pictures to him and did more than anyone else after Watson’s death to keep Watson’s name burning bright. He told everybody who would listen (including me) that Watson’s influence on mid-century British art was woefully under-recognised. He would, I hope, be very happy to know that a book on Watson is coming.

This show is fascinating; it cannot be large enough to do the artist’s oeuvre full justice, but we have to start somewhere and hopefully a bigger show will come.

Posted

Wednesday, December 4th, 2013, filed under: 20th century British art, Ghika, John Craxton, Peter Watson

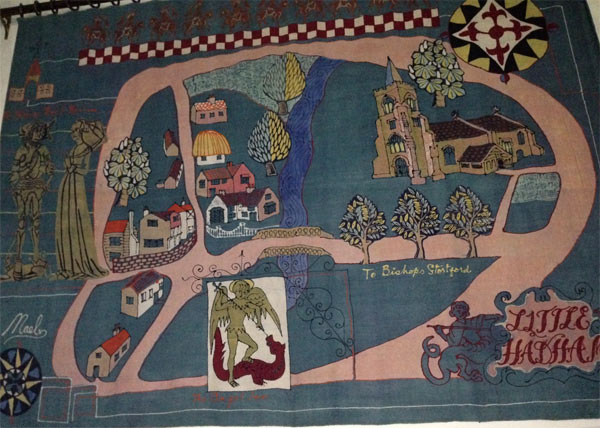

In the Nave of Little Hadham Church in Hertfordshire hangs a textile showing a stylised representation of part of the rather scattered village. It is by Michael O’Connell (1898-1976), who was a textile artist living nearby at Perry Green, where Henry Moore lived. He is described as a “pioneer in the production of textiles using dye resist techniques”. There is a website set up by his son which gives more information:

In the Nave of Little Hadham Church in Hertfordshire hangs a textile showing a stylised representation of part of the rather scattered village. It is by Michael O’Connell (1898-1976), who was a textile artist living nearby at Perry Green, where Henry Moore lived. He is described as a “pioneer in the production of textiles using dye resist techniques”. There is a website set up by his son which gives more information: